The Digital Fundraiser’s Blind Spot

You may not realize it, but you and I have blind spots. And I don’t mean metaphorically (at least not yet), I mean your eyes literally have areas where they can not see. Most of the time, our blind spots are unrecognizable—but they are very real—and I am about to prove it to you.

First, I want you to close your left eye, and with your right eye, focus on the “+” on the left side of this page. Now, slowly move the page closer to your face so that it is within 30 cm (12 inches). Did you find that the black dot on the right side of the page disappeared?

Now try this one and do the same thing: close your left eye and with your right eye focus on the black “+” on the left side of the page. When you move the page within 30 cm did the red “x” disappear revealing a solid black line?

What these simple optical illusions prove is that we all have blind spots—certain areas within our eyes that are devoid of photoreceptors. Where there are no photoreceptors, there is no data being sent to the brain, and so our brain fills in the gaps of missing information with what it thinks should be there. As you might imagine, these blind spots pose significant challenges to our perception of reality and may lead us to make poor decisions based on false assumptions.

The same is true for those of us working in the field of digital fundraising (here’s where that metaphor comes into play). As a digital fundraiser, we have metaphorical blind spots that are causing us to form false assumptions about our donors and cause us to experience less than optimal results. This is because there is a significant disconnect between you and your donor, and it is this disconnect that causes you to see things very differently.

For example, consider the design of the following email:

Looking through your digital fundraiser lens you might see an email that follows many of the best practices we have all been taught. It has the organization’s logo very large and prominently displayed at the top of the email to ensure that the recipient knows exactly who the sender is. The design of the piece is clean, makes use of an image to bring a personal face to the people being helped through the donor’s donation, and the email includes multiple opportunities to give—one at the very top (because no one really reads emails anyway), two that are hyperlinked from the text, an one more opportunity with a big clickable button at the bottom. Some of us might grimace at what seems to be too much copy in the email body, but other than that, I think we would mostly agree that this email follows many of the “best practices” of an effective email appeal.

But do you know what the potential donor sees? Unfortunately, the potential donor just sees some organization that is trying to market to them. The images, HTML formatting, and big clickable buttons are a dead giveaway that this email didn’t come from another human, it came from an email machine.

Herein lies the problem; no one wants to be marketed to, instead we want to be communicated with. So, by creating and sending a really slick, professional-looking email, this organization has intentionally put the potential donor in a defensive posture straight away. Think about it—when you feel like someone is trying to market to you how do you react? What type of barriers do you put up? Do you become skeptical? Critical? Annoyed? On some level, we have all experienced this defensive posture in response to unwelcomed marketing. The fact that we often don’t consider this when we craft our appeals is evidence of our blind spot.

Now, let me show you another email:

When I show this email to a room full of digital fundraisers, I usually get comments like this:

“This email looks unprofessional—look they don’t even hyper-link text, they just copied and pasted the raw link into the body of the text.”

“The design is boring—it lacks pictures which we all know are worth a thousand words.”

“Way too much text—no one really reads emails.”

But when a potential donor sees this email, what they see is an email that looks like what they might expect to receive from a friend, colleague, or family member. So, they open it. They read it. And they respond!

Now, I know that you might be thinking that this sounds like an interesting theory, but how do our blind spots actually impact our ability to raise funds for our organization?

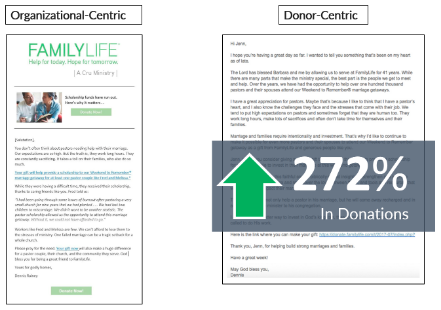

Well, the only way that we can know for sure is by testing. So that is exactly what we did. These two emails are treatments in an online fundraising experiment we conducted in our lab, experiment #6988. When put to the test in a head-to-head A/B split test, the simple, plain, boring, unprofessional version produced 272% more donations compared to the email that followed every best practice:

So, what can we take away from this experiment?

1. First, we must embrace the fact that as digital fundraisers we are all imperfect. We often fail to see exactly what our donors see, and this causes us to create campaigns that are sub-optimal. But it’s not just our blind spots we have to consider. In an upcoming webinar hosted by the DMAW on September 9 at 1:15PM ET, Nat Ward from Stand Together and I will talk about the two other challenges that we must learn to overcome (hint: one involves how we listen to our donors and the other how we speak to our donors).

2. Once we become aware of these challenges, we can then begin to overcome them. But this requires the development of two very important skills: humility and empathy. Humility is essential because when we admit we don’t always have all the answers, then we become open to embrace a new point of view—our donors’ point of view.

But humility itself is not enough, we also need to develop empathy. Empathy enables us to understand how our messages, emails, and landing pages make our donors feel. As world renowned neuroscientist, Antonio Damasio once explained, “We are not thinking machines that feel, we are feeling machines that think.” What this means is that if we can increase our capacity for empathy and hone our ability to communicate using emotions, we can more effectively speak to the part of our donors’ brains that controls decision making, and unlock more giving.

3. The final lesson we can learn from this experiment is the importance of testing. The truth is that no matter how much fundraising experience we gain, we will always have to overcome these obstacles that cause a disconnect between us and our donors. That is when we need to turn to the experts. And I am not talking about consultants or agencies, or nonprofit industry gurus. I am talking about the true experts—the donors themselves. When we learn to humble ourselves, and allow the donors to become our instructors, they will teach us everything we need to know about how to grow our fundraising.

Tim Kachuriak, Chief Innovation & Optimization Officer NextAfter